ISSUE NO. 9: MODERN DAY SLAVERY: GRAY AREAS AND MANAGEMENT APPROACHES

The emerging focus on modern slavery has highlighted abuses occurring when workers are forced to labor against their will, but our assessments reveal a much more common concern – workers laboring freely, under conditions that they may not be aware do not meet internationally-accepted fair labor practices

The conditions appear deplorable to those of us fortunate enough to work in the globe’s centers of commerce. Long hours, dangerous tasks, unclear pay at the end of the week…and no reliable means to raise a concern without fear of it resulting in your dismissal. The emerging focus on modern slavery has highlighted abuses of forcing workers to labor against their will, but our assessments reveal a much more common concern – workers laboring freely, if not with full cognizance, under conditions that do not meet internationally-accepted fair labor practices.

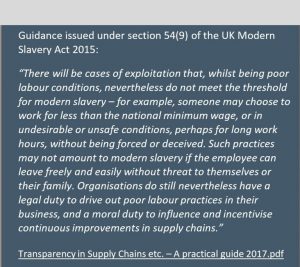

While not clear violations of modern slavery legislation, these are not conditions that any board of directors or responsible shareholder would find acceptable for their supply chain, nor would they meet the intent of most corporate ethics policies. Multi-national companies can still face material business risks related to human rights if their suppliers’ workforces are free of slave labor but replete with other fair labor violations. And yet compelling or incentivizing suppliers to advance out of this delicate and expansive “gray area” can be difficult.

WHAT IS THE GRAY AREA OF MODERN SLAVERY?

How can we recognize this gray area and what steps can be taken to influence valued suppliers to meet fair labor standards beyond those focusing on forced labor?

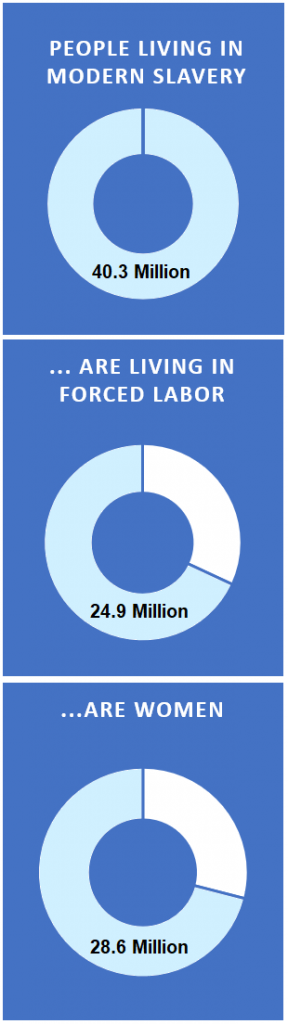

There are 40.3M people living in modern slavery today, of which 24.9M are  in forced labor and 71% are women[1]. Modern Slavery is very different from what many of us remember learning at school. Modern Slavery has been defined by several international agreements, standards and conventions[2], and covers not only slavery but also servitude, forced or compulsory labor, and human trafficking. Framing Modern Slavery in Human Right Terms we not only link it to “Freedom from Slavery” but associate it with other rights like Right to Food, Right to Rest and Leisure, Right to Adequate Standard of Living, Right to Favorable Working Conditions, Right to Just Remuneration, Right to Life, Liberty and Security of Person, Right to Freedom of Movement Freedom from Torture and Degrading Treatment.

in forced labor and 71% are women[1]. Modern Slavery is very different from what many of us remember learning at school. Modern Slavery has been defined by several international agreements, standards and conventions[2], and covers not only slavery but also servitude, forced or compulsory labor, and human trafficking. Framing Modern Slavery in Human Right Terms we not only link it to “Freedom from Slavery” but associate it with other rights like Right to Food, Right to Rest and Leisure, Right to Adequate Standard of Living, Right to Favorable Working Conditions, Right to Just Remuneration, Right to Life, Liberty and Security of Person, Right to Freedom of Movement Freedom from Torture and Degrading Treatment.

For labor intensive industries, third party suppliers are likely to be located in developing countries where labor is cheap, unemployment is high and labor standards are weak. Often these conditions are accompanied by little to no government oversight. In our field assessments we frequently encounter workers who are desperate for a job, even if it means choosing to work under exploitative conditions, because a job that does not meet international fair labor standards is better than no job at all. We call this “the gray area” of business and human rights, where certain situations are clearly identified as unfair labor practices but not outright slavery.

The ILO has provided specific definitions for Forced or Compulsory Labor as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily” (ILO Forced Labour Convention, 1930 No. 29, Art. 2.1). Taking this definition as our benchmark and comparing it against what we have seen in recent assessments, we see that workers are “free” to leave, nobody is “forcing” them to stay, their papers are not being “retained”, nor are they under any fear of “punishment”. The common denominator in all of our assessments has been the dire and pervasive state of poverty of many of these workers, their lack of formal training and their desperate need to make a living. Poverty forces many to accept harsh working conditions where they are underpaid, work long hours and can never attain an adequate standard of living.

WHAT DOES THE GRAY AREA LOOK LIKE?

So, what does this look like? When should auditors look further into a situation that is regarded as “normal” in the local context and not out of compliance with local laws, but “unfair” in the eyes of international labor standards adopted as policy by global companies and expected to be met by their boards, investors and customers? Below are examples of unfair labor practices we have observed during assessments that are not considered “analogous to slavery” but fall within the gray area of human rights, requiring practitioners to investigate each unique set of circumstances further:

- Right to Just Remuneration: Workers in some of the operations we have assessed are not paid the minimum salary agreed in their contracts but rather receive a production-based cash compensation. In one specific case, in a labor-intensive industry, the employer changed the terms of payment— basing income on production targets that were only established at the end of the month. Not only was this modality not mentioned in the contracts, but it also meant that employees worked longer hours to try to meet an invisible production target that they may or may not attain.

- Right to Favorable Working Conditions: Overtime legislation in developing countries is often not regulated or remunerated. In a specific case, we identified that support staff made up of cleaners and cooks worked an average 14 hours a day to ensure breakfast, lunch and dinner were ready, rooms and bathrooms cleaned, and clothes washed for the workers. Even though their contracts stipulated 8-hour work days, the 6 additional hours worked per day were not remunerated because, as we often heard, “nobody pays over-time” in that specific industry. This reality had escaped many auditors before who in the past had only interviewed the mill workers, forgetting completely about the support staff that is also needed to run the industrial process.

- Awareness and Fringe Benefits: A common finding in the assessments we have conducted is how little employees know about their rights beyond minimum wage and collective agreement obligations. Faced with this disadvantage, some employers in the supply chain turn a blind eye on benefits that should be paid. Because third and fourth tier supplier wages are often paid in cash, it is difficult to track whether contributions have been made to social security and other fringe benefits.

Operations that are located in isolated or rural settings often require a rotational work scheme where employees are boarded at the facility and return home every so often. In some parts of the world it is common for the employer to commit to provide transportation to-from the point of hire or a designated center when operating in remote areas. However, we have witnessed cases in which transportation is treated informally and not as a contractual commitment. Returning home when working on a rotational basis is sometimes a luxury many workers can’t afford.

- Audits and compliance monitoring: We have noted that most tier-one suppliers have an internal audit system in place, but often, these are focused on worker safety and the “check-in-the-box” system allows for little to no-interaction with employees to discuss other fair labor considerations – like healthy working conditions, number of hours worked and worker disciplinary practices.

- Grievance mechanism: The ILO[3] states that: 1) every worker should have the right to submit a grievance without suffering any prejudice whatsoever as a result 2) any grievances submitted should be examined via an effective procedure which is open to all workers. Unfortunately, we have encountered situations where employers a) do not understand the right and advantages of having a grievance mechanism and b) they see it as an unnecessary avenue where false or irreverent claims are made.

The question we often get asked is what is the company’s responsibility  for demanding that its third-party contractors not only meet anti-slavery standards, but also meet other international fair labor standards?

for demanding that its third-party contractors not only meet anti-slavery standards, but also meet other international fair labor standards?

Company policy can provide some clarity on answering this question. Some companies have Supplier Standards of Conduct where they make a specific commitment to the responsible management of the supply chain. More commonly referenced is the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work or the Global Sullivan Principles, which recognize collective bargaining, non-discrimination, adequate compensation and a healthy and safe work environment as fundamental rights along with the elimination of forced and child labor. Also referenced are the Sustainable Development Goals in human rights policies, hence covering their commitment to ensure the promotion of decent work for all.

HOW CAN COMPANIES MANAGE RISKS IN THE GRAY AREA?

Still, influencing suppliers to upgrade labor conditions to meet international standards – when they are not in violation of local laws or facing push-back from workers – can be difficult. But there are come practices companies can take internally to avoid finding themselves in the “gray-area” where they may be supporting conditions inconsistent with their policies or even worse, contributing to human rights violations. Here are a few:

- Know Your Supplier (KYS). Ensure your Company has a mechanism to ensure the responsible management of suppliers and that screening processes go beyond check-in-the-box answers. Warren Buffet once said “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to lose it. If you think about that, you will do things differently.”

- Identify Your Soft Spots. Conduct a risk assessment of the company’s industry, geography and type of work third-party suppliers would be performing. For example, where does your company have third-party suppliers in areas with weak labor laws, high numbers of unemployed and low-skilled workers, low living wages and labor-intensive industries?

- Share Your Story. Make valued suppliers aware why it is important for your company’s investors and customers to ensure that operations throughout its supply chain meet global fair labor standards, and how this will guide future procurement decisions.

- Build Supplier Capacity. Offer valued suppliers training and tools (such as a grievance mechanism template) to promote the application of international fair labor standards – without violating local regulations or putting responsible suppliers at a disadvantage

- Incentivize Good Performance. Offer bonuses or other incentives to those suppliers who are shown by on-going assessments to meet international fair labor standards (beyond not employing slave labor), even if not required to do so by local laws.

- Check the Contracts. Work with qualified legal counsel to evaluate the fair labor provisions in contracts between first and second tier suppliers and to determine if it is feasible to encourage such language to be strengthened if needed.

- Manage Labor Risk. Integrate fair labor and other human rights into the company’s risk management framework and identify from the beginning who are the rights-holders at risk and the degree to which their rights may be negatively affected.

Recent legislation has catalyzed opportunities for global companies to identify and reduce the presence of modern slavery in their supply chains. But experience shows that focusing just on eradicating slavery can leave companies open less obvious but more prevalent fair labor risks – those gray areas in which workplace conditions violate fair labor practices other than actual forced labor. As consumer and investor demand for fair labor products grows, global producers will do well to ensure their supply chain labor management programs are comprehensive enough to tend to the critical gray area that lies beyond the formal definition of slavery.

[1] 2018 Global Slavery Index. https://www.globalslaveryindex.org/2018/findings/global-findings/

[2] UN Declaration of Human Rights – Article 4. http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/index.html

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDG 5.2 and SDG 8.7 and SDG 16.2). https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

ILO Forced Labor Convention (1930) (No.29) – Article 1. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C029

Abolition of Forced Labor Convention (1957) (No.105) – Article 1. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C105

ILO Forced Labor Convention (Supplementary Measures) Recommendation, 2014 – Article 1. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:P029

ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy. https://www.ilo.org/empent/areas/mne-declaration/lang–en/index.htm

United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/documents/publications/GuidingprinciplesBusinesshr_eN.pdf

California Transparency in Supply Chains Act, 2010. https://oag.ca.gov/SB657

UK Modern Slavery Act, 2015. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/30/contents/enacted

Australia Modern Slavery Bill, 2018. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/Bills_Search_Results/Result?bId=r6148

[3] ILO’s Examination of Grievances Recommendation, 1967 (No. 130). https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:R130

_____________________________________________

Acorn International LLC delivers social and environmental risk management consulting services to the extractive industries and investors worldwide. We work with local partners in over 80 countries worldwide. Use of these local specialists is paramount, particularly in developing countries, where information is often scarce, second-hand, and unreliable. We look forward to engaging in continuous improvement for the industry and building capacity with our partners.

News & Notes

Acorn International

1702 Taylor St, Suite 200B

Houston, TX 77007, USA

1213 Purchase St

New Bedford, MA 02740, USA