ISSUE NO. 35: OIL & GAS AND NGOS: NEW RULES OF ENGAGEMENT?

Update: 10 Years Ago We Were Thinking…

It has been just about ten years since we published this short piece on relationships between oil and gas companies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Did we get it right? We are reposting with a few observations:

- These ideas about ‘rules of engagement’ apply more broadly than strictly to ‘oil and gas’

- NGOs remain an important part of civil society, but we do not see them as ‘gatekeepers’ to relationships with community members

- Transparency and proactive social performance is even more important now than it was in 2011. In future posts we’ll discuss the evolution of FPIC (free, prior and informed consent) and the latest version of the Equator Principles.

- Accountability (regarding companies, NGOs, or any other actors) should be understood as a ‘two-way’ commitment

ACORN NOTE (2011) – OIL & GAS AND NGOS: NEW RULES OF ENGAGEMENT?

How ‘engaged’ are oil companies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs)? Are the relationships between these actors exclusively and energetically adversarial, or have new forms of interaction emerged? This Acorn Note focuses on Corporate-NGO engagement during major oil and gas (O&G) projects and suggests some developing models for mutually valuable relationships. We include recommendations for project managers based on our ‘field experience’ working with NGOs and companies on some of the world’s largest oil and gas projects.

BACKGROUND

Expectations have continued to rise over recent years regarding how major O&G projects analyze, manage and communicate about their social and environmental performance. NGOs are among the most interested and active stakeholders, particularly with regard to projects located in developing regions, and those undertaken in countries with poor governance, financial transparency and human rights records. Around the world, NGOs increasingly expect meaningful and prolonged company engagement. No longer is it typical that a government-issued permit marks the sole purpose of – and mutually satisfactory end to – project-driven stakeholder engagement.

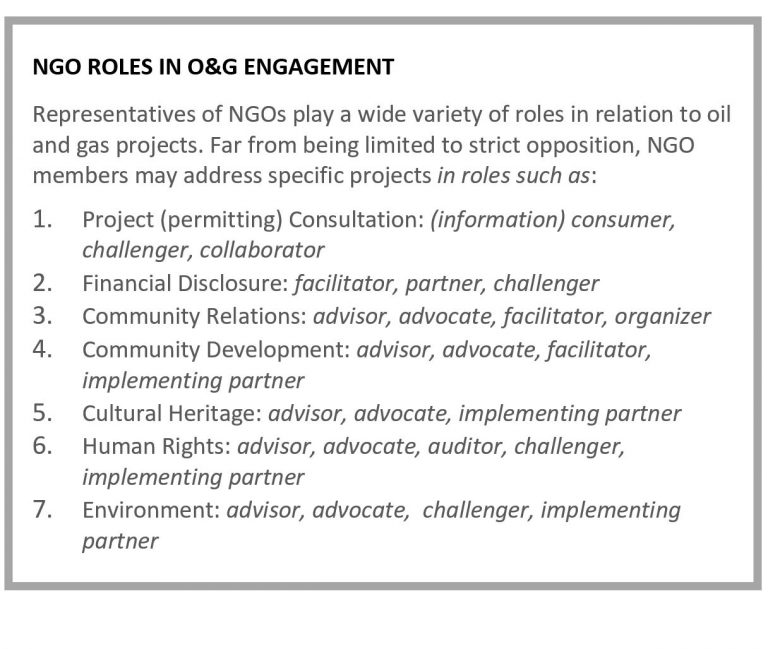

NGO and O&G company relationships are commonly portrayed as a tug-of-war, a battle of opposing sides. But while some ‘watch-dog’ NGOs are quite adamantly and categorically opposed to oil companies and associated projects, this strident position is far from universal. Increasingly, one can find recognition among civil society actors that O&G projects are often uniquely positioned to make significant positive contributions to local development. Many NGO representatives would agree with the assessment of a researcher who noted that oil and gas “footprints can be seen in developing countries in the transfer of foreign direct investment (FDI), skills, and technology; as major employers of labor; and accounting for a large proportion of state revenue. Their contribution to development in many countries via programs in education, health, commerce, agriculture, transport, construction, etc., cannot be ignored.”[1]

But growing recognition of such potential development contributions has hardly marked the end of NGO campaigning and opposition. Rather, some civil society organizations continue to target oil companies, and seek to influence their actions through strategies such as “boycotts, networking, publicity, sit-ins, walk-outs, lobbying, litigation, socially responsible investment, people’s development plans, public hearings…blockades, barricades, seizures and closures, etc., in campaigns (that) involved ethical issues such as environmental, health, safety, corruption, climate change and human right abuses.”[2] For their part, companies are increasingly recognizing that engagement is not only hard to avoid, but difficult to systematize given that there is no ubiquitous NGO ‘position’ regarding O&G projects. Instead, corporations are developing distinct strategies for dealing with priority groups and the networks that exist between these groups. As a result, one can observe a spectrum of joint activities, ranging from the required and often perfunctory sharing of project information to the joint pursuit of full collaboration and mutual value. And increasingly, some of this interaction is driven by engagement requirements imposed by financial institutions.

LENDER REQUIREMENTS – SOCIAL PERFORMANCE AND NGO INTERACTION

Social performance analysis of major infrastructure companies and projects is no longer limited to ethical funds and ‘socially responsible investors’. Mainstream investors and companies which provide financial advisory services are paying more attention to the social performance of companies wherever they operate not only for ethical reasons, but also because they believe that environmental and social performance can affect a project’s delivery on time and on budget, overall operational success, and long term financial viability. Lenders continue to become more demanding: the Equator Principles[3] and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) Performance Standards[4] established key stipulations for (financed) project compliance, ranging from applying impact assessments to building appropriate impact management systems. They also include specific guidelines for company-stakeholder interaction.

In both the Equator Principles and the Performance Standards, stakeholder engagement is explicitly required. Equator Bank financing is dependent upon consultation “in a structured and culturally appropriate manner…(F)or projects with (potentially) significant adverse impacts…the process will ensure their free, prior and informed consultation and facilitate their informed participation as a means to establish…whether a project has adequately incorporated affected communities’ concerns.”[5] This language is also featured in the IFC’s performance standard 1, which requires that “…for projects with significant adverse impacts…Informed participation involves organized and iterative consultation, leading to the client’s incorporating into their decision-making process the views of the affected communities on matters that affect them directly, such as proposed mitigation measures, the sharing of development benefits and opportunities…disclosure should occur early in the Social and Environmental Assessment process and in any event before the project construction commences, and on an ongoing basis.”[6]

Of course, while NGOs draw membership from project-affected populations, they are organizations, not communities. Nonetheless, lender-required engagement will often feature such groups because they routinely act as representatives (self-appointed or otherwise) of affected communities. Equally important, NGOs have legitimate interests in project design, impact management and natural resource protection and use. NGO representatives are also potential facilitators of information exchange between communities and companies. Optimally, they are groups well positioned to help companies understand local communities and indigenous populations, including past history and current expectations, how authority systems are structured, and how to ensure that the company is able to partner appropriately with the community for its development. NGOs can help enlist community support as a partner in the project, even as they advocate for specific company performance, provided they are seen as an honest broker by both company and community. The basis for such positive engagement is transparency – sharing of information, plans, priorities, and expectations.

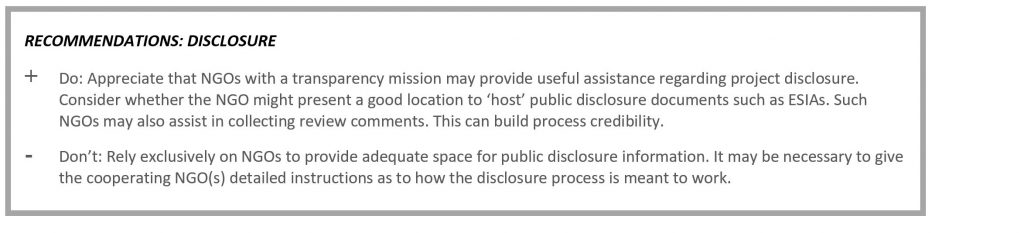

PROJECT INFORMATION DISCLOSURE

‘Consultation and Disclosure’ is often the primary model for NGO-O&G interaction. NGOs and civil society stakeholders remain a key participant in the public meetings and reviews of project plans that are required in environmental and social impact assessments (ESIAs). In most cases, the input that companies receive during consultation must be addressed before required government permits are issued. There are many NGOs and civil society groups that provide copious feedback to companies as they attempt to improve and fine-tune the environmental and social aspects of their projects. Unsurprisingly, the feedback provided by such groups varies considerably in quality – from timely and valuable, to regrettably uninformed and lacking in useful insight.

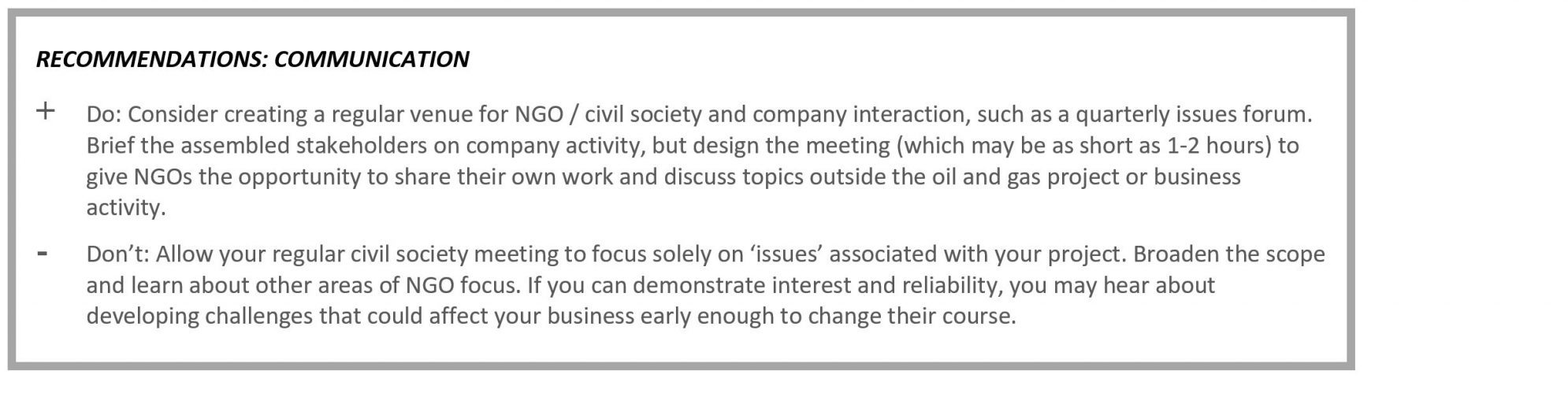

In some cases, NGOs may exaggerate the degree to which they represent communities or local stakeholders purportedly affected by proposed project activities. Nonetheless, meaningful O&G-NGO interaction quite often commences during formal ‘public consultation’ activities, and provides a baseline transparency tool for both company and civil society. Properly managed, communication about project activities allows companies one-time, ad hoc or regular insight regarding their reputation and the level of support/concern they have earned with stakeholders. NGOs, particularly when they approach the consultation in a constructive manner, may achieve a primary goal: gaining a ‘seat at the table’ or some degree of influence over decisions affecting environment and society. They may also help community members understand where project activities are – or are not – having an impact on their lives. However, this important and useful interaction may place the company in challenging positions, particularly regarding corporate influence, revenue and transparency.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE AND TRANSPARENCY

There is growing interest and challenge from NGOs and other stakeholders on issues which may lie beyond companies’ direct control and only within their limited influence. These include issues like revenue management (how the host country spends the income from the company or sector), and how the presence of a business may affect host communities’ access to their basic human rights, such as freedom of expression or movement. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), launched in 2002 at the World Summit for Sustainable Development, is now endorsed by 50 of the world’s largest oil, gas and mining companies. It has established a new baseline of transparency and engagement regarding material oil, gas and mining payments to governments. It is now possible for NGOs or other interested parties to access considerable amounts of information regarding projects and financial payments.

Yet this successful focus on one side of the resource revenue equation – transfers to government – has been followed by an even more challenging civil society request: to enlist company support in helping pressure governments to account for how these resource revenues are being spent. As revenue disclosure continues to be a key issue for O&G, NGOs can be found playing myriad roles: challenging government and companies to be more transparent, facilitating dialogue between company, government and civil society regarding revenue, and partnering with companies to design the means of disclosure. A similarly broad range of NGO roles exists regarding Oil and Gas community investment.

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

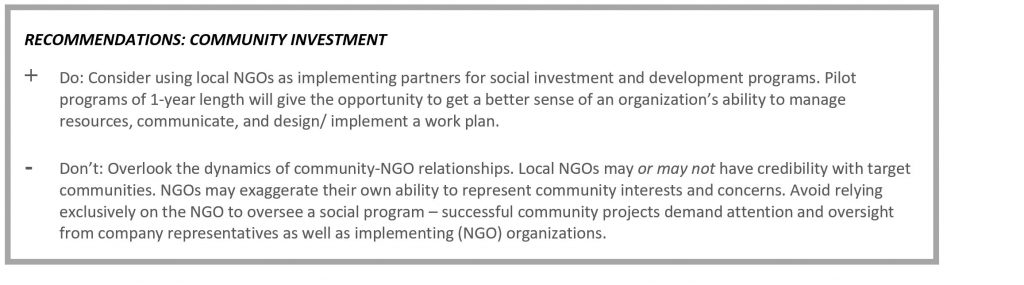

As noted above, NGOs can play a particularly useful role in helping communities and company representatives understand each other’s plans, interests, concerns, expectations and priorities. This understanding is crucial to O&G-sponsored community development programs. Successful delivery of oil and gas projects – offshore and onshore – often depends not only on exceptional engineering and project management, but on the social ‘license to operate’ (LTO) that is granted by host communities. Social LTO rests heavily on the degree to which companies manage their impacts, meet their obligations and contribute to the growth of the community. Local community members often have substantial expectations regarding company-sponsored community initiatives; management of such projects may fall beyond the expertise and/or resources of oil and gas project staff.

NGOs have come to play important roles in helping O&G projects meet community development goals. As implementing partners, they may contract directly with companies to deliver development projects. They may also play an advisory role – helping both companies and community groups understand how to best employ O&G resources and expertise in service of sustainable community development. They may advocate with local government and business community members to join O&G community project initiatives and help build development economies of scale. They may even facilitate dialogue between company and community about the roles that business can and cannot take on, helping to manage expectations. In such cases, NGOs begin to play the role of partner – to both community and company.

NGO-O&G PARTNERSHIP

There are numerous examples of NGOs and O&G companies moving beyond hostile interactions to models approaching partnership:

- A major pipeline project saw NGOs taking on crucial financial and human rights consultations with landowners

- NGOs around the world have lent their expertise to SME development efforts specifically tuned to O&G supply chain requirements

- Cultural heritage partnerships have formed between O&G projects and NGOs so that companies may more efficiently implement their projects without causing harm to archeological or cultural artifacts

- Microfinance projects funded by O&G but implemented by NGOs have provided useful elements in investment ‘exit strategies’

- Environmental NGOs have assisted in impact management planning and implementation (e.g., spill response and cleanup) in host communities

- Community NGOs have helped deliver information about safety and environment on behalf of, and alongside, O&G companies

No doubt NGO and O&G relationships will remain contentious, but the tension of balancing interests can be productive to those who understand and manage it well. The confrontational watch-dog role favored by many NGO representatives has an important place in public discourse. Oil and gas companies are starting to learn how to make use of the valuable inputs that some NGOs provide to their projects. A growing cadre of NGOs recognize that there are increasing opportunities for them to act as ‘local partners’, able to have real input and meaningful influence as major O&G projects unfold. With the right guidance and commitment to open, productive relationships, one can reasonably hope that this trend – engagement for ‘mutual advantage’ – will continue to gain momentum.

[1] Tuodolo, Felix, Corporate Social Responsibility: Between Civil Society and the Oil Industry in the Developing World, ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 2009, 8 (3), 530-541. [2] Ibid, pg. 532. [3] See http://www.equator-principles.com [4] https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/Topics_Ext_Content/IFC_External_Corporate_Site/Sustainability-At-IFC/Policies-Standards/Performance-Standards [5] This quote came from an earlier version than the current EP4, which can be found at https://equator-principles.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/The-Equator-Principles-July-2020-v2.pdf [6] This quote came from an earlier version than the current IFC PS1, which can be found at https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/sustainability-at-ifc/policies-standards/performance-standards/ps1

News & Notes

Acorn International

1702 Taylor St, Suite 200B

Houston, TX 77007, USA

1213 Purchase St

New Bedford, MA 02740, USA