ISSUE NO. 33: THE TWO CULTURES: MINING VERSUS EVERYDAY PEOPLE AND WHAT MINERS SHOULD DO ABOUT IT – PART TWO

Two factors dominate the mining industry’s DNA – one business-based and the other from science. Both are mindsets with unique assumptions, concepts and ways of thinking. They define the industry’s internal culture, and therefore the ‘brand’ in the public perception, for better or worse.

The business-based factor is rational, goal-driven and competitive. It pairs with the deeply rooted scientific mindset. Science is based on logic and planning and is supported by a linear and outcome-focused culture. It is time dependent, rule-focused and assumes that everyone does or should think and act from a consistent set of principles. These principles are seen as ‘natural’. For miners, the world is thus systematic, rational, predictable and binary. This creates black and white thinking with little room for the subjective. In a way, this puts us, as miners, at odds with the way of thinking and viewing the world by most of the rest of humanity!

I would describe this mining mindset as a ‘hyper-engineered’ approach to the world. Everything is orderly and in its place; communication based on an open perspective of alternatives with vagaries and grey areas is not especially welcome.

Science as an approach has created wonderful technological improvements and brought about enormous leaps for the benefit of mankind. Issues emerge when an endeavor like mining bumps into the world of human relationships and that world slowly stirs and begins to ask questions and starts to bite back.

SOCIAL REALITY

Good human relationships require accepting the ambiguity in how and why things happen in the world. Effective communication involves give and take, not just one-way linear progressions. Answers have endless possibilities on a spectrum, not an either-or response. This facilitates a goal whose purpose is to create a process and build relationships – an engagement that is not just tactical and outcome-oriented. Absolutes are out; relativities are the order of the day. This can be hard for some of our technical, science-minded colleagues in mining to grasp. It’s uncomfortable for traditionalists accustomed to communicating in a finite universe with provable answers.

The irony is that mining is an ancient and fundamental human activity, yet it is disconnected from its end production and use. Most miners concentrate on production – “moving dirt” – ignoring the fact that we extract a product that everyone knows, has or covets. The end users don’t really enter into our language or thinking, thereby leaving out the vital, end-user stakeholder. Our focus and language put us at odds with them. We create an ever-widening gulf, ignoring our commonalities. So, we find ourselves misunderstood, unappreciated and mischaracterized. We lament:

- “The end users value our products but scorn us!”

- “Our reputation doesn’t align with the customer need.”

- “Our industry doesn’t get credit for its necessity much less its technical advances toward sustainability.”

Maybe this is because closing in on sustainable development in mining does not merely involve technical changes and achievements – it also requires building and maintaining sustainable human relationships through meaningful communication. However, most people either do not know what that involves, or they do not believe the assertion.

Time and time again, mining companies have problems with groups ranging from the public at large to host communities. We wonder why. Until we as miners realize that our business and science perspective is not the only way to see the world and until we develop empathy for the messy complexity that is human relations, we will not make much progress in bridging the divide.

LANGUAGE CONTRASTS

What is the language of our environmental discourse in the mining industry? Who is its audience? What are the languages and media of our critics? What of the general public? Who is doing what to whom and to what effect? Are we talking past each other and is the general public–the community at large—missing out altogether – to our detriment?

I examined a set of environment statements from a range of American and Australian mining companies and contrasted them with statements about environment and mining by leading NGO critics. These examples were drawn from a representative sample of company and NGO reports and web sites. Amazingly all are on the same issues and the same sites.

KEYWORDS: AN UNCOMMON LANGUAGE DIVIDES US

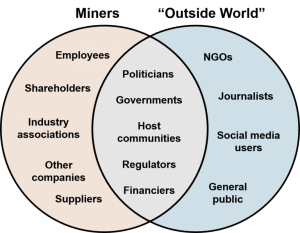

AUDIENCES: POLARIZED BUT OVERLAPPING

BEYOND LANGUAGE, THE POWER OF PICTURES

What about the look and feel of these documents, their presentation? Here too the contrast is stark. At one extreme we have some corporate reports on environment with no photographs, complex diagrams, and heavy slabs of text. At the other extreme, we have NGO web sites with nothing more than nice nature shots on their front pages backed with a few choices and snappy ‘facts’ from the same tired ‘experts’.

With many of the mining reports, you get the feeling that it is a case of “This is science, and we will overwhelm you with its goodness and truth”. “Trust us.” The other side doesn’t have to do much more than instill doubt in the readers’ minds where uncertainty usually already exists.

The visuals tell a story too. Images of nature in all its glory and smiling onlookers often contrast with huge, bare muddy holes in the ground and big heavy machinery and shiny technology.

Big holes and machinery are the industry stock in trade and considered to represent major achievements. For the uninitiated, the shock is substantial on seeing the results and means of our work. (It is most instructive to take ‘novices’ to a mine site now and then to realize what we take for granted. They are usually dumbfounded at the scale of an open-pit mine.)

The open-pit at the Martha Mine at Waihi in New Zealand is a case in point. At one point in the late 1990s, the same aerial photograph of the primary pit (which is in the middle of the town) was shown on Martha’s web site (‘Look at how much earth we have moved and how many local jobs we have created!’) and on a local environmental defense group’s web site (‘Do you want this to happen in your town?!).

With mining environmental reports, our, perhaps, naïve, aim is to tell people about our performance in the best way we know how: in line with the best science, our industry can offer. Our antagonists use a streamlined, method: smooth and simple campaigns. The singular objective is to sow doubt and remove trust in the mining industry.

In handling the environment as an issue and our impacts upon it, I would not say that major resource companies are not doing excellent work. As I said, when modern scientific methods and technology are applied to, for example, an environmental impact issue it is usually not long before ways around problems are found.

We have come an astonishing distance in this and with our environmental reporting (despite what I said above). The last five years have seen a remarkable improvement. Reports by companies such as Anglo-American, Rio Tinto, BHP, Newmont and Barrick are now comprehensive, widely available in hard copy and on the web; they are performance-based, transparent about problems and progress, and there is usually outside objective monitoring and auditing. What more could people want, one might ask?

A COMMON LANGUAGE FOR DIALOGUE?

There was once an episode of the television series, ‘Star Trek’ (‘Loud as a Whisper’) where warring factions on the planet Solais V seek assistance from an outside mediator to help achieve peace. However, the languages of the two groups are mutually unintelligible. The mediator, Riva, is deaf (though telepathic). In a stroke of negotiating genius, he has each side learn sign language and, partly due to them finally having a common means of communication, peace gets a chance.

Closer to home is another example from my own experience as an anthropologist. In Cape York Peninsula, in far North Queensland Australia, some of the Aboriginal groups speak up to eight different dialects or languages. In conversation with a person whose main language is different from your own, you would speak their language and they would speak yours. Diplomatic and linguistic civility! Miners and mining’s critics need to learn more about each other and engage in dialogue based wherever possible on common understandings, words and goals.

SO, HOW CAN WE AS MINERS BEGIN TO CHANGE OUR OWN CULTURE? SOME SUGGESTIONS:

- Recognize that we have our own vocabulary and jargon and that not everyone is part of this. Investigate and try to use the language of the stakeholder, the ‘other’. Put yourself in “their shoes”.

- Encourage our critics to learn about the mining side of things.

- Seek out and develop common objectives and work on them. These might include raising awareness about the need for our products, joint efforts towards sustainable development to ensure future supply and local development: from “mortal enemies to common goals”.

- Bring stakeholders into our dilemma of being a technical enterprise in a non-technical world. Work towards a common understanding of a limited resource that can be developed at the outset via a closed loop environmental objective.

- Think “outside the mine fence”. Realize that mining is no longer a closed system. There is an external world out there that impacts our business. We need to better understand and engage with it.

While I recognize that mining has considerably improved working relationships with its stakeholders including antagonists, we can do better. We work closer now with environmental, health, education and other groups on the “host community” issues. We can go further, though, by recognizing and being constantly mindful of our language and our representation as we grapple with living in a complex, multi-faceted world. Good for people and good for business.

News & Notes

Acorn International

1702 Taylor St, Suite 200B

Houston, TX 77007, USA

1213 Purchase St

New Bedford, MA 02740, USA